Looking ahead

“For now, the Oyu Tolgoi agreement is not benefiting Mongolian citizens. It is good to attract foreign investment but that doesn’t mean foreign investment should only benefit the foreign side.” – Battumur Baagaa, a member of the Mongolian parliamentary working group, 21 November 2019 – [expand title=”source”]Source:

https://www.mining.com/web/rio-tinto-faces-having-to-renegotiate-terms-of-mongolian-copper-project/, retrieved Dec 13, 2019[/expand]

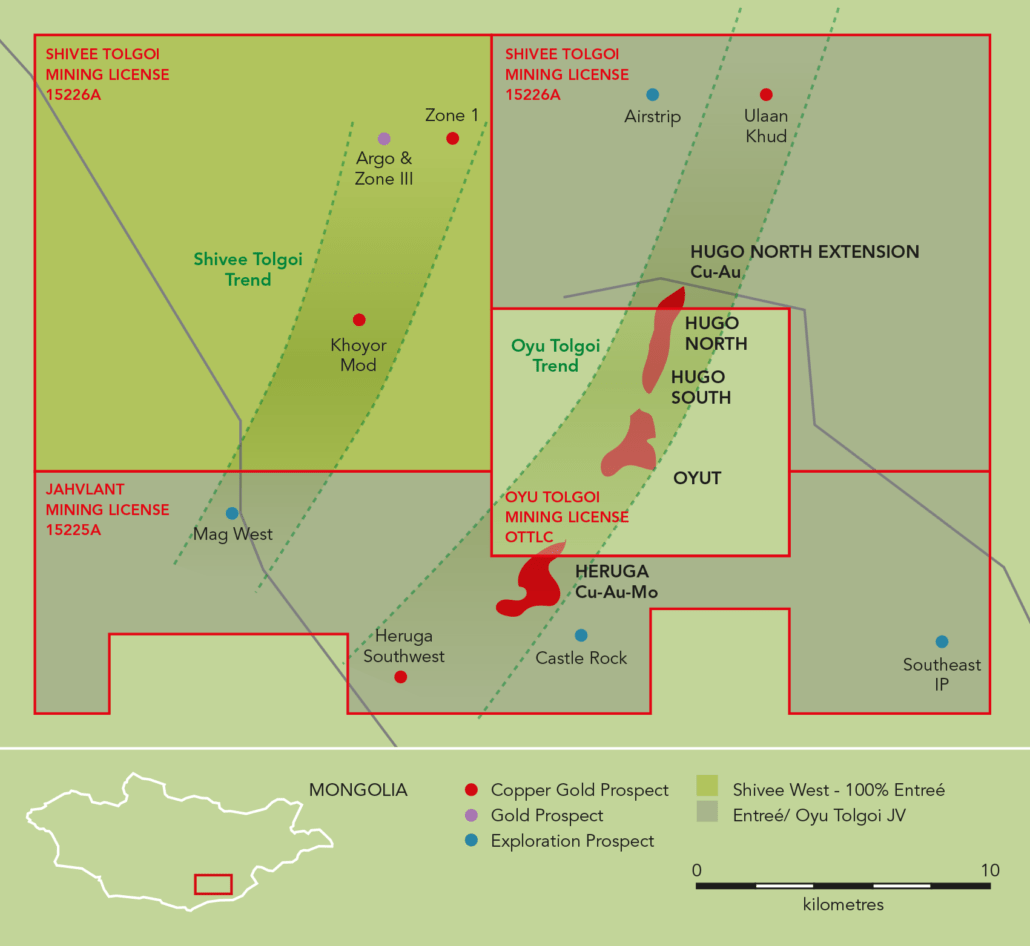

Ever since 2003, when negotiations over the Investment Agreement began, Mongolian civil society and politicians have questioned their access to the revenues from the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine and demanded more sovereignty over its resources.

Our report ‘Undermining Mongolia‘ confirms that Mongolians have ample reason to question the intent of the OT investment agreement, as well as the very limited benefits they may possibly receive. Mongolia signed an Investment Agreement in 2009 that privileges “western” corporate interests by offering generous corporate oriented incentives that do not fill public coffers. We show that the negotiations were riddled with power inequities and pressure to comply with international expectations, in a context dramatically restructured by institutional reform from a state-led to a market economy, narrowly focused on mining.

The disruption of the lives and livelihoods of nomadic herder communities living in the area around Oyu Tolgoi, and the impact on soil and water, was recognised when an agreement was reached between herders, local government and OT LLC to address complaints in 2017. Nevertheless, the monitoring phase was closed in March 2019 and the ecological degradation and social fragmentation have not been resolved.

The stranglehold of ISDS

The Mongolian government is hand bound in the demands it can make of Rio Tinto and its fellow investors. This is due to so-called Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) clauses enshrined in both the Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement and in many Bilateral Investment Treaties, such as the one Mongolia has with the Netherlands. An ISDS clause allows investors to sue host governments in the case of investment disputes. The legal challenge is then brought before an independent court where judges decide whether the investment protection articles enshrined in the applicable ISDS clause were violated.

Originally intended to stop arbitrary abuse by states singling out foreign investments, ISDS has devolved into a mechanism that allows corporations to interfere with states’ sovereign right to legislate in their people’s public interest. The ISDS system has been found to be one-sided – only allowing corporation to sue states, but not the other way around – inscrutable and costly, and it allows corporate interests to challenge legitimate public interest legislation. With global legal and financial architecture determined by a very corporate aligned definition of development, the outcome is seldom positive for resource-rich countries like Mongolia.

The role of international financial institutions

For this to change, we need to turn to the role played by ‘Western’ governments and Bretton Woods institutions in Mongolia’s development. The World Bank and IMF were instrumental in the liberalisation of Mongolia’s markets, and stimulated the country’s focus on mining as its principal vehicle for development by creating an enabling context for foreign capital to exploit the extractive potential of Mongolia. This was done despite the detailed World Bank commissioned 2003 Extractive Industries Review (EIR) that details how resource wealth does not easily translate into sustainable development, especially because contracts signed between governments and corporate parties inhibit the possibility of environmental and social regulation in the future.

While the World Bank ushered Mongolia further into the mining industry, and helped remove its public checks and balances, the US colluded with corporate interests to pressure Mongolia to lower its demands for revenue. Exploiting both Mongolia’s desire for so-called ‘third neighbours’ – political counterweights to Russian and Chinese influence in the country – as well as its dependence on IMF finance, the US and its allies were apparently successful in furthering their commercial interests. As a result, a country that was first directed towards letting foreign companies enter its mining industry in order to achieve economic development has since then been pressured out of protecting its interests in negotiations with those same mining companies.

The scale of Oyu Tolgoi, its finite mineral deposit, and the enormous social-ecological impact, demand urgent public attention and debate on the desirability of allowing large-scale mineral exploitation under such disadvantageous conditions. The repeated lowering of the withholding tax has significantly decreased any income the government of Mongolia can expect to receive from the mine, while the interest paid on the loans to Oyu Tolgoi will likely limit the mine’s profitability and dividends Mongolia can expect to receive in future. If the current arrangements continue, it seems unlikely that the Mongolian people will see much benefit at all from the Oyu Tolgoi mine.

Legally looting natural resources

For Mongolians to have access to, and control over their resources, the globally legitimized looting of it by multinationals would have to be challenged and stopped. This means that we have to demand that notions of ‘good governance’ and ‘rule of law’ are redefined away from corporate interest and profit seeking and towards a healthy planet for the benefit of all.

The Oyu Tolgoi project hijacked Mongolian policy with its fiscal stabilization and arbitration clauses supported by international investment treaties and taxation agreements, consolidated by the too-large-to-fail financing structure signed in 2015, and the weight of the western international community behind the agreement, both politically and financially. The global economic and regulatory context, with its legal and institutional frameworks, is geared towards a development paradigm that favours economic growth and free capital flows. This translates into an emphasis on a safe investment climate, rather than a healthy environment for people and planet.

Recommendations

In support for more democratic control over resources, we present a number of recommendations that can be found in our report ‘Undermining Mongolia‘. In short we call for:

- The review of the agreements to ensure more revenue capture for the Mongolian people;

- A renegotiation of Bilateral Investment Treaties to safeguard public interest legislations;

- Increased respect for Mongolian nomadic cultural and unique ecology;

- Awareness and implementation of the EIR recommendations by all diplomatic and financial actors involved in extractive industries, in particular regarding economic diversification and community decision-making and revenue sharing;

- Alignment of national and international economic interests with sustainable development, and in line with the 2015 Paris Agreements, instead of prioritising economic growth for few at the cost of many.