Oyu Tolgoi unearthed

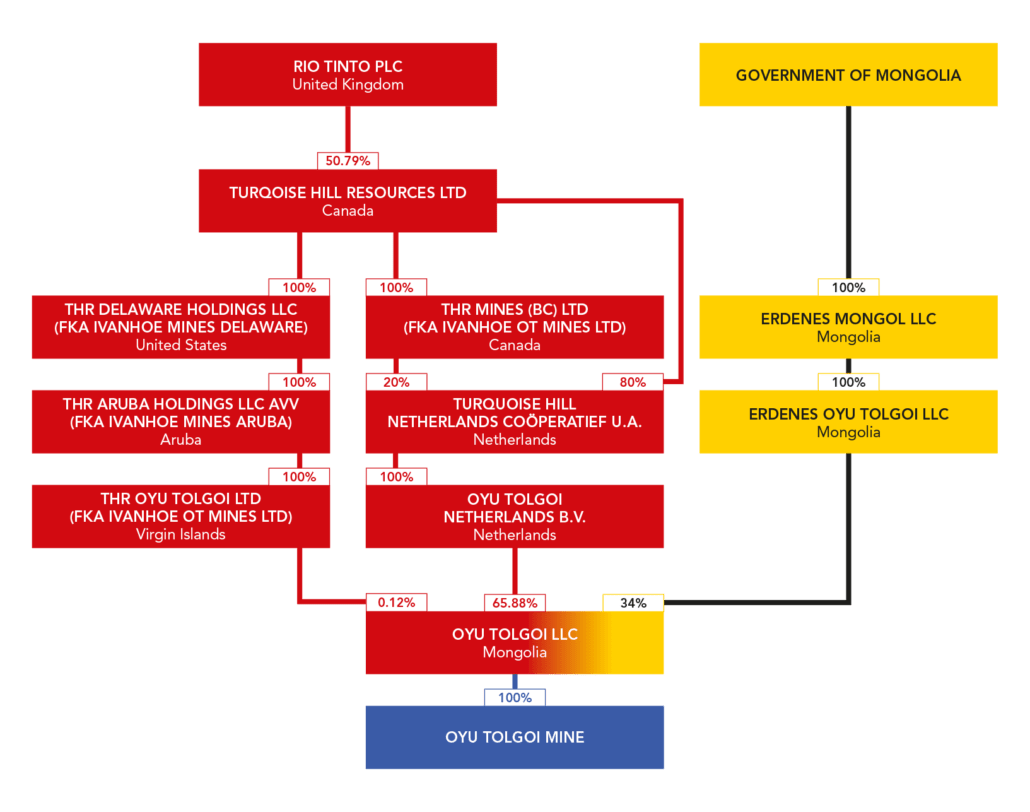

“Because the Mongolian government is committed to bearing 34 percent of all the mine’s costs, as costs rise so do the country’s debts with Rio Tinto. It will take us decades to pay back the loan. We expected to see the first dividends on the mine in 2019. But it turns out it will be 20 or 30 years before we see a share of the profit.” – Otgochuluu Chuluuntseren, then Director General of the Mongolian Ministry of Mining’s Department of Strategic Policy, 2013 – [expand title=”source”]Zand, B. August 7, 2013, https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/mining-the-gobi-desert-rio-tinto-and-mongolia-fight-over-profits-a-915021-2.html, (accessed December 8, 2017).[/expand]

Development and impact of the mine

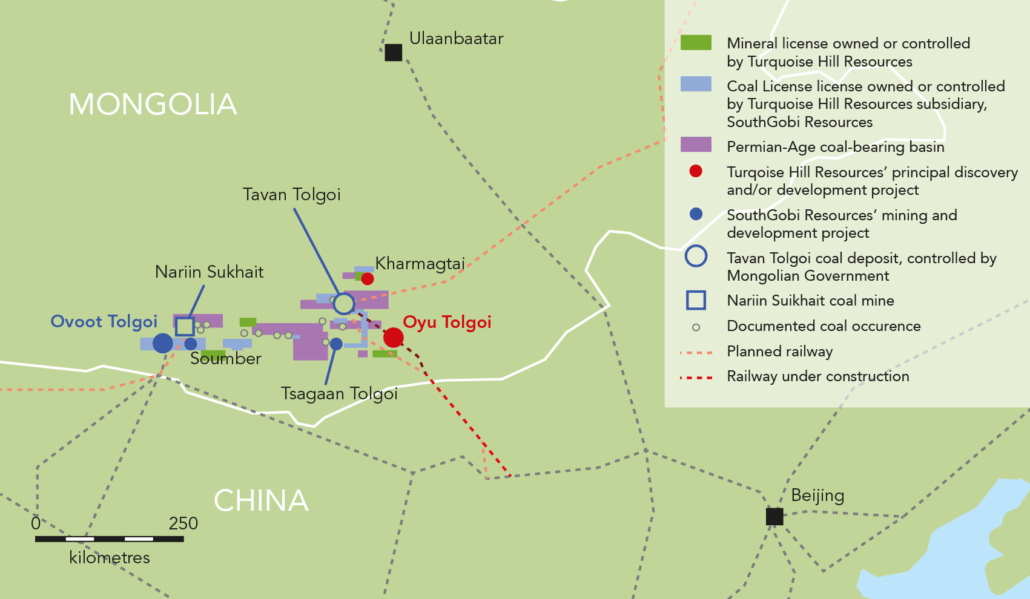

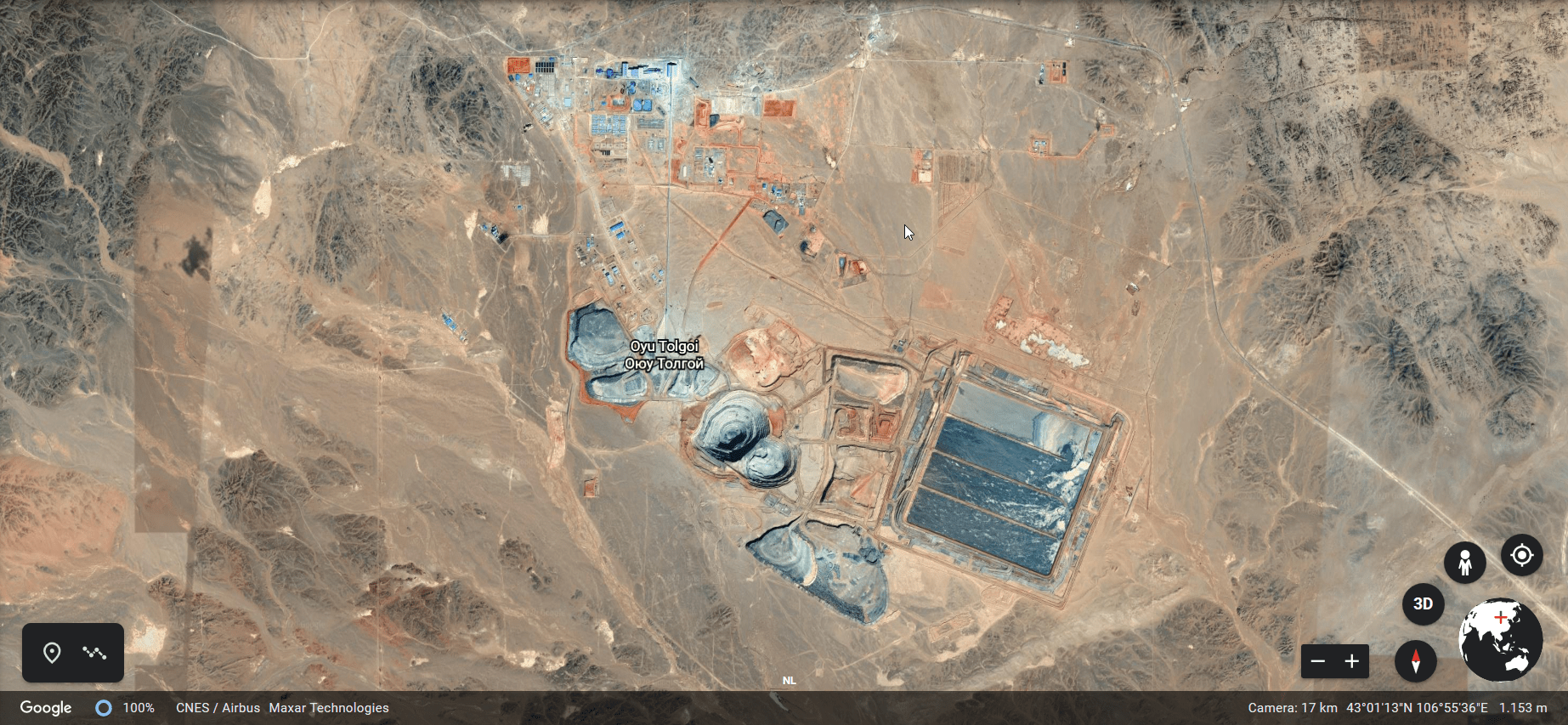

In 2010, construction work began on Mongolia’s flagship copper and gold mine after high-grade copper and gold deposits were identified in 2001. The project was named Oyu Tolgoi – which means ‘Turquoise Hill’ in Mongolian – in a nod towards the local traditions it threatened to undermine.

To make way for the mother of all mines, the Undai River had to be diverted, affecting both water and pasture resources – driving local herdsmen from their traditional grazing land, as well as threatening endangered plant and animal species. Besides, mining, construction works, and heavy transport are generating increased amounts of dust, which is [expand title=”detrimental to the health and everyday life of both herders and cattle”]References:

- Troy Sternberg and Mona Edwards (2017). Desert Dust and Health: A Central Asian Review and Steppe Case Study, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14(11), 1342; https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/14/11/1342/htm

- Sara L. Jackson (2015) Dusty roads and disconnections: Perceptions of dust from unpaved mining roads in Mongolia’s South Gobi province, Geoforum 66 (2015) 94–105. https://www.academia.edu/17805001/Dusty_roads_and_disconnections_Perceptions_of_dust_from_unpaved_mining_roads_in_Mongolia_s_South_Gobi_province

[/expand]

Video by Abhi Singh / Accountability Counsel, via YouTube

In 2012, supported by the NGOs OT Watch and Gobi Soil, herders filed two complaints against the International Finance Corporation (IFC), one of the investors in the mine. The parties entered a dispute resolution process that resulted in an agreement in 2017.

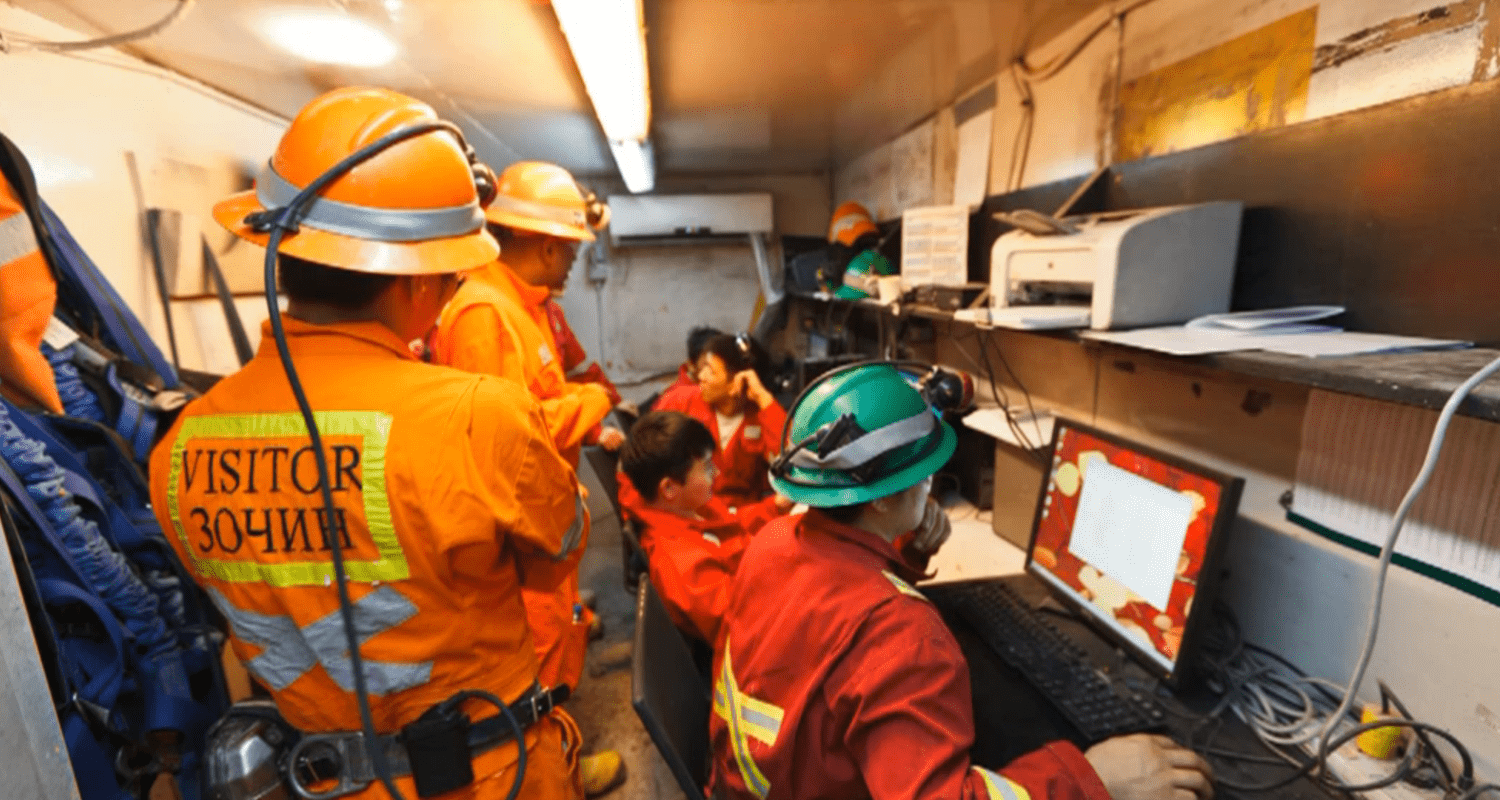

Underground at Oyu Tolgoi. Stills from video by Simon Blears, via Vimeo CC

Production issues

The whole Oyu Tolgoi project consists of two phases. Phase 1 is an open pit mine, phase 2 is an underground operation. In its first year of operation in 2013, the open pit mine produced a staggering 77,000 tonnes of copper and almost 4,500 kg of gold; within three years, those rates had more than doubled. Based on average prices for 2016, Oyu Tolgoi production would have been valued at US$ 979 million for copper and US$ 342 million for gold.

For the past seven years, the minerals have been pouring over the border into neighbouring China, where demand for copper and gold are at their highest. By July 2018, the total shipment of concentrate, processed from the ore taken from the open pit, had reached 4 million tonnes. As well as hundreds of kilometres of underground tunnels, the project also includes an airport, a 70km water pipeline, paved roads and power lines that run to the Chinese border.

The underground operation is where 80% of the mine’s value is purportedly located. Production was planned to start in 2019, and the combined production from open pit and underground was predicted to amount to more than 500,000 tonnes of concentrate annually. In October 2018, Turquoise Hills announced production would be delayed until 2021, and in July 2019, Rio Tinto announced further delays of at least another 16 months with extra costs reaching US$ 1.9 billion.

To access the underground copper and gold ore, block caving mining methods are used, reaching up to 1,300 metres below ground and involving 200 kilometres of tunnels and 10 kilometres of conveyer belt. The huge scale of the operation and the use of block cave mining carry the danger of subsidence, and the surface above the extraction zone is likely to remain permanently unstable.

Satellite view of the Oyu Tolgoi mining complex, captured 13 February 2020. Courtesy Google, CNES / Airbus, Maxar Technologies.

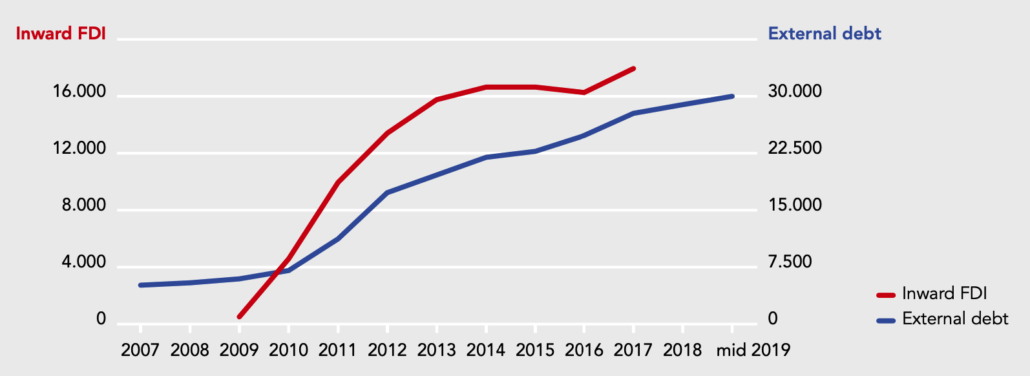

Lagging revenues

The significance of Oyu Tolgoi for Mongolia cannot be underestimated in an economy where mining revenues account for 90% of exports. With its open pit and underground facilities running at full tilt, it is projected to generate 25-30% of Mongolia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2020. And yet, the country’s population is unlikely to see much profit for up to 30 years.

The reality is that Mongolia never had a fair chance to negotiate a deal that would serve the people of Mongolia. External factors such as the political instability and manoeuvring within Mongolia, and the 2007/2008 global financial crisis, left Mongolia with its back against the wall. Underpinning these forces was a structural reorganisation of the Mongolian economy and society after its independence from the Soviet Union that left Mongolia with a myopic focus on mining. This was followed by policy reforms that smoothed the way for overseas investment and favoured corporate interests over public social and environmental concerns. Policies that were supposed to support ‘good governance’ have, in practice, dismantled public checks and balances.